skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Making a Home: Japanese Contemporary Artists in New York

Making a Home, a fascinating, multi-sensory survey of Japanese artists living in New York City, is an invigorating and often whimsically fun exploration of the play between these two distinctive cultures. Loosely organized by curator Eric C. Shiner into six thematic currents, the show displays an incredible diversity while investigating issues such as consumerism, intimacy, mourning, and the artistic process itself. While weaker individual pieces sometimes fall behind the venturesome pace and ill-begotten curatorial choices interfere with some of the strongest work, the overall impression is one of sprightly intellectual curiosity and effervescent cultural mingling.

Immediately upon entering the Japan Society, the viewer is confronted with My Mommy is Beautiful, a wall-sized piece by Yoko Ono that invites the audience to record memories of their loved ones upon a neutral white background. While any exhibition claiming to be a comprehensive presentation of New York-based Japanese artists must include Ono, I found her piece to be trite and cloyingly sentimental. I took part in Ono’s memory-celebration, and it felt nice to do so, but it left no lasting impression and said nothing profound about the role of remembrance as a ubiquitous artistic practice. That concept could be fascinating if it was given a more thoughtful treatment, but it remains syrupy and undeveloped in its current incarnation.

The most striking work of the show is also the easiest to miss due to some perplexing curatorial choices. Silent Staircase, by Yasunao Tone, uses modern ultra-directional speakers to create a contained, surreal soundscape within the bustling lobby of the Japan Society. As you walk under Tone’s creation, the speakers negate the surrounding babble of the lobby’s waterfall, creating an invisible cone of insulating, otherworldly noise that doesn’t so much engulf the viewer as transport them. As part of the Building an Environment portion of the exhibition, Tone’s technological alchemy uses sound to ‘build’ an environment while simultaneously mystifying its conventional attributes. The piece is the most conceptually innovative and playful treatment of the theme in the exhibition, though it is hard to spot due to insufficient labeling and an unexplainable separation from the rest of the show.

The conceptual landscapes of Tōru Hayashi, also inexplicably secreted away from the body of the exhibition, nonetheless remain the most striking work of the Referencing the Landscape exhibition theme. Hayashi’s Equivocal Landscape consists of hundreds of tiny, simplified drawings of trees that float amid the white void of his sketchbook pages. They have an undeniably endearing quality, adorably captivating while avoiding the saccharine sweetness of Ono’s work. But in their resemblance to hieroglyphics and their serialized presentation, the drawings also suggest a runic language of mystical universality. They capture the essential meaning of the trees, interpreting the subject through its most fundamental characteristics.

Hayashi expands this investigation of his surroundings in the Metropolis Mandala Series, which he completes after exploring a city for days. He searches for illusive changes in the metropolitan landscape, seeking indications of a city’s intrinsic character and how it subtly shifts over time. Hayashi’s mandalas are prismatic, vaguely spiritual records of these impressions. The artist explains, “The term mandala can be translated as ‘integration of truth.’ I reinterpreted it to demonstrate the ‘intergration of time.’”

Reminiscent of the painterly musings of Paul Klee, the pieces produce a cosmology of fleeting sensation and perceptual mystery. Hayashi has created mandalas of New York, Paris, Tokyo, and Delhi, finding metaphysical calm within the globalist trends of transience and migration. The subtle expressionism and precious scale of his work are refreshingly unique in a show replete with grandiose, room-sized installations.

Of the larger installations, Hiroshi Sunairi’s White Elephant stands out for its ghostly starkness and elegiac immediacy. Part of the Coping with Loss exhibition theme, the piece presents a life-sized porcelain reproduction of an adolescent elephant, shattered into withered pieces and strewn about a black vacuum. Viewers are drawn to walk amongst the artist’s charnel house and contemplate the sepulchral stillness of the fragmented goliath. Sunairi’s mournful response to the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the piece explores the capriciousness of life and death with the staid elegance of a Dutch still life.

Yumi Kōri’s installation Shinkai uses sound and light to create a transcendental experience of space and time. Shinkai, which means “deep sea,” morphs the gallery space into an ethereal realm filled with crystalline bubbles and undulating red lights. Ambient sounds submerse the viewer and reinforce the deep ocean effect. As part of the Meditative Space exhibition theme, Kōri’s installation makes clever use of mirrors to stretch the visual stratum into the infinite, presenting a calming but altogether alien sanctum. Confounding the viewer’s relationship to his environment, the piece creates a nebulous, amniotic otherworld that invites meditative disengagement from everyday reality.

The exhibition’s overriding theme of making a home results in a myriad of imaginative treatments of space, ranging from the metaphysical landscapes of Tōru Hayashi to Hiroshi Sunairi’s mournful Golgotha. Although similar currents are difficult to conjure, many of these artists make ingenious use of technology and Eastern religious practices to strategize an increasingly global world. The exhibition, though sometimes hindered by perplexing curatorial decisions, offers a fantastic survey of these trans-cultural visual strategies and the Japanese New Yorkers who adopt them.

Making a Home: Japanese Contemporary Artists in New York

Japan Society

Through January 13, 2008

And Kara Walker...

Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love

Investigating the popular reception of Kara Walker’s work is a strange exercise of virulently opposite perspectives, different generations, and a national culture that often can’t confront, let alone comprehend, a potently lingering racism or the ultra-lacerating history that led to it. The most famous response came in 1997, when Betye Saar notoriously exclaimed that Walker’s work used “derogatory [stereotypes] of pickaninnies, sambos, and mulatto slave mistresses… for the amusement and the investment of the white art establishment.” Saar, who is from an earlier generation of African American artists, accused Walker of betraying her race by reinvigorating these deeply racist symbols and presenting them in a sexually debased, sado-masochistic plea for artistic recognition.

While I would never deny Saar her opinion, I believe that she stops short from piercing the deeper reality of Walker’s work. While Walker does portray negative African American stereotypes with a vaguely defined but unrestrained self-loathing, she does so to re-problematize a race debate that has grown far too complacent in recent days. Her work, explored in a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American art, reveals the sad, infuriating complexity of a toxic racism that gave rise to American slavery and continues, subtly hidden and often unchecked, into the present day.

Immediately upon entering the exhibition, the viewer is assaulted by The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven, 1995. A wall-sized panorama of silhouettes cut from black paper, the work plays out like a fever dream of psychological debasement and historical festering. Three slave women suckle one another while an infant goes unfed; a small black child defecates uncontrollably beside a white southern belle who swings an axe upon herself; a repugnantly obese, crippled slave master sodomizes a young slave while impaling another with a sword. Walker’s warped treatment of the antebellum South has all the smothering paranoia of a nightmare and the immediacy of a howl.

The viewer’s shadow intermingles with the silhouettes, suggesting a discomforting personal involvement in Walker’s narrative of race psychosis. We become inextricably bound to the work, as we are inextricably bound to the pandemic that spawned it. A later silhouette piece, Slavery! Slavery! Presenting a GRAND and LIFELIKE Panoramic Journey…, 1997, achieves an even greater and more disturbing synthesis of viewer and work by wrapping completely around a circular room. The space becomes a nexus of racist self-loathing and psychosexual atavism, inundating and inescapable.

A later series of collage pieces violently debunk the problematic narrative recounted by Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War, culling imagery from the history’s pages and combining it with pornographic photos of African American women. The works, completed from 2001 to 2005, juxtapose the typically noble treatment of white Civil War generals found in Harper’s with the dregs of black sexual exploitation. The most striking piece presents a nude black woman, legs spread, with imagery of Civil War battle covering her mouth, breasts, and genitals. Walker suggests that the female African American body is bitterly contested territory, enslaved and objectified by white sexual aggression.

The most effecting work of the show is Walker’s video pieces, which have a raw immediacy that heightens the operatic theatricality already present in the artist’s best work. 8 Possible Beginnings of: The Creation of African-America, a Moving Picture by Kara E. Walker, 2005, is a form of surreal revisionist history, an often leeringly hideous shadow play that reveals the agonizing psychological legacy of slavery and its greatest benefactor, King Cotton. The piece is purposely reminiscent of Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith’s silent epic that recounted the ascendancy of the Ku Klux Klan as a noble, ordering influence over a barbarous, morally vacant throng of freed slaves. Walker steals Griffith’s blatantly racist mythology and turns it upon itself in a rending display of historical sarcasm.

In the video’s central sequence, a black slave and his white master fellate one another while cotton sprites dance gleefully above. The master “impregnates” the slave with a cotton blossom, spawning the bizarrely misshapen byproduct of King Cotton and slavery. The child, a mutant, decaying reflection of the joyous cotton sprites, is Walker’s symbol for the psychological fissure at the heart of America’s racial history. It is the buried cancer, malignant and seemingly inoperable, that her work makes dreadfully clear.

The silhouette is Walker’s weapon of choice, and there is no doubt that she wields it with incredible anger. They are certainly visually arresting, and it is tempting to appreciate them on aesthetic grounds alone. But their macabre content and Walker’s barely concealed fury defuse any purely formal enjoyment. The characters confront the viewer with forceful baseness and deadly vulgarity, demanding to be seen and understood as both offensive stereotypes and symptoms of an insidious cultural disease.

While Saar would argue that the artist is giving these images new life, Walker suggests that they have always been part of the national id, putrefying in our collective unconscious like a rotten tooth. For Walker, while the disease remains, there will always be a need to appropriate its most repugnant imagery for use in vicious retaliation. As she exclaims in one of her text pieces, “I make art foranyone whos forgot what it feels like to put up a fight…”

Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love

The Whitney Museum of American Art

October 11, 2007 - February 3, 2008

And Richard Prince...

Richard Prince: American Spirituality

American Spirituality, Richard Prince’s massive retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum, carries on like a gibbering, vulgarian soothsayer, joyfully setting loose a legion of inner demons that the American psyche would sooner repress than confront. Gleefully offensive and intellectually compelling in equal measure, the work tackles a slew of complex issues. Class, gender, sexuality, celebrity, and the artist’s quixotic self-absorption violently compete for attention. While flashes of brilliant insight intermittently flourish in Prince’s cultural grotesque, the show’s unwieldy scope fails to coalesce in any meaningful fashion. At some point the relentless barrage of Prince’s critique veers into the realm of self-parody and never finds its way out again.

The basis of Prince’s work is appropriation, his most infamous artistic innovation and weapon of choice for cultural dissection. Beginning in 1977, the artist began rephotographing advertising images and presenting them as fine art, imploding the idea of originality while revealing the cultural mythos imbedded in the original images. Preferring to work in series, Prince pulls back the rock of the American façade and presents, with almost scientific serialization, the subterranean cultural currents that flow beneath.

While the retrospective features numerous series of Prince’s appropriation photography, the most compelling are the Cowboys and Girlfriends. Juxtaposed and intermingled near the middle of the show, both series illuminate embarrassingly complex truths hidden within deceptively simple imagery. The Cowboys, derived from Marlboro cigarette advertisements of the 1980s, scrutinize the myth of the impossibly masculine, resolutely rugged cattleman. Through repositioning such macho symbols as the cowboy, the horse, and the boundless wilderness, Prince explores the male desire for gender identity through masculine potency and confounds Marlboro’s attempt to link virility with an incredibly unhealthy product. Prince explains, “A rephotograph is essentially an appropriation of what’s already real about an existing image and an attempt to add on or additionalize this reality onto something more real, a virtuoso real.”

The Girlfriend series dissembles a similar myth, the motorcycle as a sacristy for the vaunted American notion of individual freedom. The frontier desperado finds his modern-day counterpart in the motorcyclist, represented in the media as ‘One-percenter’ outlaws who renounce social structure for hedonism and transience. While morally problematic for most Americans, the narrative emblematized by the Hell’s Angels reinforces cherished ideals of personal freedom and mobility. The girlfriends, propped awkwardly against this symbol of masculine prerogative, lose their humanity and become extensions of the fabrication. Through enlargement, Prince emphasizes the licentious desperation of the masculine fantasy and the discomforting vulnerability of the female attempt to fulfill it.

The artist elaborates upon this theme in a new series of works that appropriate the Abstract Expressionist milieu of Willem de Kooning’s Women paintings of 1950. Abstract Expressionism itself was an intensely masculine affair, replete with hard drinking, chain smoking, and a vigorous amount of male self-importance. Female artists such as Lee Krasner were celebrated less than their male counterparts. De Kooning’s Women are savage, punishing affairs, the figures barely emerging from the gestural violence as hideous parodies of the female form.

Prince borrows de Kooning’s forms and desecrates them with male and female cutouts from pornographic magazines. The artist co-ops the uniqueness of the Abstract Expressionist gesture, then befouls it with the nadir of low culture imagery. Through a brilliant act of visual contamination, Prince simultaneously draws out the vicious subtext of the earlier works, confounds their stature as high art, and critiques a sexist dynamic that withheld open appreciation for female artists during the 1950s.

Prince elicited a similar art historical interaction with his Monochrome Joke paintings, produced between 1987 and 1989. The formula is simple: take a monochrome canvas and slap a recycled, borscht-belt joke in the center. Recalling the post-minimal aesthetic of Ellsworth Kelly but eschewing Kelly’s lyrically personal forms, Prince’s paintings embody the banality of mass-production. The austere surfaces and the mawkish, hand-me-down humor suggest the hokey knick-knacks you might find at an airport gift shop. Referred to as “antimasterpieces” in the exhibition catalogue, these works casually upset the core values of art and collapse traditional ideas of greatness and historical relevance.

As the 1990s drew to a close, Prince amplified the self-critique of the Joke paintings by increasing their scale and dropping the monochrome canvas. The jokes now float among fields of ethereal, gently shifting pigment or organized grids of expressionist gesture. Stenciled over themselves repeatedly, they produce worn, spectral palimpsests of Prince’s formulaic system. The grid and the stencil, both references to Jasper Johns, are strategies that reveal a procedural repetition and sabotage notions of expressionist epiphany and emotional involvement.

Later Joke paintings use cancelled checks as a backdrop for a more pointed lampoon of unique artistic identity and capitalist greed. The checks, each personalized with Jimmi Hendrix imagery and Prince’s signature, give a record of the artist’s purchases. In an increasingly corporate world that values and defines a person by what he is capable of buying, the checks could be read as a catalogue to Prince’s essential being. The artist slyly allows this consumer mentality to invade his work and reveals its soulless prerogative.

But while all of this is riveting on a work-by-work basis, the exhibition as a whole comes up short in a number of ways. It’s said that Nancy Spector, chief curator of the Guggenheim Museum, worked in close collaboration with Prince while organizing the show. While it’s clear that Spector wants to do justice to the full breadth of Prince’s oeuvre, the finished product could use a few less pieces and many more editorial compromises. There’s simply too much here, organized in too rambling a fashion, for the show to find cohesive footing.

Depending on how you count, there are no less than nine series in the show, each an exuberant rumination on art, society, and any number of other American cultural shibboleths. The exhibition could drop a couple threads – the Cars sculptures and Upstate photographs come immediately to mind – without interfering with its total impact. For a show labeled American Spirituality, it does its best to meet that concept head-on with enough intellectual tenacity, thematic repetition, and ironic grotesquery to send the viewer into metacritical exhaustion. If Prince and Spector had been more careful with their choices, this frustratingly longwinded retrospective could have been more than the grueling sum of its many, many parts.

Richard Prince: American Spirituality

The Guggenheim Museum

September 28, 2007 - January 9, 2008

Sorry for the long wait between updates. It's been a choppy couple of months. One of my students happened to remind me that the blog still exists, so I'm back with a few new reviews (well, at least new to the blog). Unfortunately, some of the shows aren't around anymore, but at least you can get an idea of what was there. On to Neo Rausch...

Neo Rausch at the Met - para

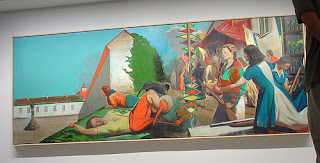

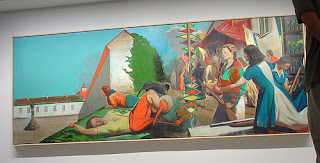

Who are the ghostly, self-absorbed band of characters central to Neo Rausch’s new show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art? What are they preparing for, and what would they say to one another if they noticed each other’s presence? Why are they dressed like turn of the century dandies, picturesque peasant workers, and vaguely socialist firemen? Rausch, who generated an entirely new cast for this series, isn’t incredibly distracted with predetermined answers to these questions. The artist is more intrigued with the how of these eccentrics: how they come into being and how their visual alchemy creates a quixotic mysticism. As the figures emerge from the lunar miasma of Rausch’s subconscious, they produce a seductively mysterious narrative crammed with enigmatic juxtapositions. Rausch, who titled the show with the incomplete prefix para, is interested in the cascade of associations that his surrealist theater creates within the viewer.

Rausch was trained in Leipzig, where he lived under the East German Communist regime until its collapse in 1989. The Leipzig Academy, which had been in the thrall of figurative painting for nearly two centuries, was abruptly introduced to the conceptual theories and new media techniques of Josef Beuys. Suddenly, artists began to eschew painting and the figure as prosaic and antiquarian. “Painting was the most boring department in the school, and everyone was making jokes about the painters, because they were so old-fashioned in the East German style,” explains Ricarda Roggan, a Dresden-born photographer.

However, Germany has witnessed a return of figurative painting with the emergence of the New Leipzig School, a group of artists who resisted the conceptual legacy of Beuys. Rausch, the most significant figure of the resurgence, refers to himself as “conservative” and “romantic.” He works in the same melancholic, expressionist heritage that includes such essentially German painters as Max Beckman, Ernst Kirchner, and Georg Baselitz. These artists all share a preoccupation with the expressive power of the figure and an obsession with German cultural identity, often characterized with brooding isolation, instinctual naturalism, and the tortured relation between the internal self and an often pernicious external world.

Rausch’s Germanic roots are most on display in Die Fuge (The Gap), an epic phantasm of a painting that mournfully articulates the traumatic schism Germany endured after World War II. Expressions of divide fill the work, from the massive trench that literally dissects that composition to a pair of eerily floating doppelgangers, severed by an effulgent bolt of lightning. A band of fireman dressed in matching uniforms and wrestle fruitlessly with a serpentine hose like a social realist mutation of the Laocoön. Their incompetence reflects the miscarriage of the East German Communist regime, whose ineffectual brand of socialism resulted in economic ruin and cultural decadence. Rausch’s use of stark, deteriorating architectural facades also recalls the economic frailty of Leipzig, where pandemic unemployment has littered the city with abandoned factories.

Rausch interest in his cultural past finds expression in Waten auf die Barbaren (Writing for the Barbarians), an image of confounding theatricality and acidic color that presents a group of peasants preparing for a fair. The villagers wear costumes of minotaurs and other chimerical creatures, instilling the proceedings with an oddly portentous air. While the festivities commence, an ostracized townsman is left bound to a sacrificial pyre, presumably to be killed in an act of grizzly immolation. That the other villagers are seemingly unaware of his imminent fate only heightens the painting’s dreadful foreboding, suggesting the façade of willful German naiveté that permitted Nazism and the Holocaust to rage unopposed for so many years.

The looming but nebulous threat of violence is reminiscent of earlier surrealist painting, especially the work of Max Ernst. Ernst, a fellow German who served during World War I, manipulated similar juxtapositions of strange, dream-bred imagery to release the logically devoid subconscious and induce feelings of spectacular unease. While Rausch’s imagery is less overtly fantastical, his foggy milieu is a direct descendent of Ernst’s surrealist phantasmagoria. Vorort (Suburb) exemplifies Rausch’s subtler approach, which is more emotionally suggestive than forcefully evocative. As a jumbled throng of townspeople set fire to flags under a romantically gloomy dusk sky, a nuclear warhead lies calmly isolated opposite their mounting furor. The dormant but massively deadly potential of the warhead stands in stark, lunatic contrast to the villagers and their comparatively benign riot.

Rausch is fascinated by imagery of curtains, fake facades, and costumed players. He sets the stage, then lets his medley of vaguely-defined characters and absurd imagery coalesce into a deranged opera of cultural ambivalence and psychological unrest. “For me, the function of painting… is to work with myths,” the artist explains. “I try to create a widespread system where impulses are trapped. A microclimate comes into being.” Rausch’s surrealist casuistry tells it slant, reinvigorating his German artistic heritage with refreshing wit and insight. The ambiguous theatrics of his fractured narratives explore the mythic German consciousness, defined visually over the past century by the tortured figural paintings of Beckman, Kirchner, Baselitz, and many others. The unique strength of Rausch’s work lies in its ability to pierce this mythology and project it, psychologically fragmented, as a theater of fever dreams and violent fantasies.

Neo Rausch at the Met- para

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

May 27, 2007 - October 14, 2007