Here's my first review. Unfortunately, the show has already finished its run, but I still thought it was a good place to start. Enjoy.

Richard Serra - Sculpture: Forty Years

“This isn’t here to teach you anything. It’s your experience and what thoughts it engenders. That’s your private participation with this work.”

Richard Serra, who is loquacious but emotionally guarded through most of the audio tour of his major retrospective, breaks into an abrupt and barely noticeable surge as he insists upon the experiential nature of his work. It’s a quick moment, as the artist immediately returns to a more restrained tone, but it offers valuable insight into Serra’s artistic process and his attitude towards the exhibition. The show, which stands among the largest and most expensive the Museum of Modern Art has ever executed, explores Serra’s work from the relatively small rubber and lead pieces of his early career to three massive yet curiously graceful steel environments made particularly for this retrospective.

As a form of experiential observation, the show is certainly impressive. Deftly creating physical and temporal space through these enormously heavy materials, the work has a persistent, immutable quality which avoids didacticism while still demanding the viewer fulfill the “private participation” described by Serra. At times, however, the dual narratives of the exhibition’s laborious and time-consuming installation and Serra’s well-publicized arrogance tend to overwhelm the staid elegance of the work itself. This nagging preoccupation most plagues the largest pieces, and it is these moments that the exhibition is at its least successful.

Chronologically, the show begins on the sixth floor. Serra’s earlier sculptural works simultaneously occupy and redefine a series of rooms, and it is here that his work finds its surest footing. Delineator, 1974-1975, consists of two immense steel plates installed at right angles to each another, one on the ceiling and one on the floor. Unlike many of Serra’s sculptures, this work remains mostly unweathered and maintains a dark, reflective surface. The uniformity of tone urges the viewer to forego observation of the piece as a physical object and concentrate on how it characterizes the space in which it’s exhibited. The margins, contours, and volume of the room become increasingly apparent, and the viewer engenders a heightened awareness of his relation to this specific space in time. In a sense, the viewer’s physical dialogue with the steel plates transforms the room itself into the subject of the work. The sculpture’s capacity to create and emphasize volume is fascinating in that it essentially reframes the role of the museum as an active participant rather than a simple medium of exhibition. Elaborating upon this idea, Serra stated, “As you walk towards its center, the piece functions either centrifugally or centripetally; you’re forced to acknowledge the space above, below, right, left, north, east, south, west, up, down.”

This hypersensitivity to one’s surroundings recalls the minimalist sculpture of artist such as Tony Smith, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris, contemporaries of Serra’s who also believed that experience of art should reach beyond easy, reverential observation. Resisting the formal pedagogies of Clement Greenberg, who urged artists “to render substance entirely optical,” these artists implored viewers to become physically intimate with their work. Stressing this interaction, the experience of their art eschews observation for an active exploration of form, material, and space. Serra has been working in much the same vein for the last four decades, continuously experimenting with unique forms, formidably severe mediums, and an increasingly monumental scale that would reek of sculptural braggadocio if it weren’t so consistently awe-inspiring.

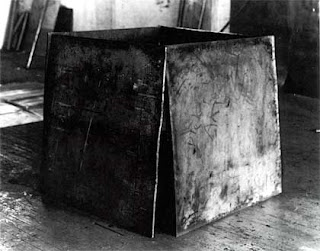

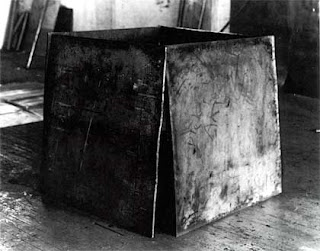

One Ton Prop (House of Cards), 1969, achieves a similar experiential materiality through very different formal means. Although the piece consists of four lead slabs with a collective weight of one ton, it achieves a paradoxical delicacy through Serra’s seemingly precarious mode of presentation. The four segments simply lean against one another, confounding expectations of the material’s profound mass while suggesting a tenuous, fragile weightlessness. Describing his process, the artist has said, “If the pieces are equally balanced, the weight is canceled out, you have no thought of tension nor of gravity.” The power of Serra’s Prop Pieces lies in the tension created during the realization of this balance, matching rugged firmness with anxious sensitivity, titanic mass with ethereal space. Unfortunately, the inherent tension of these pieces and instability it suggests has led the museum to separate them from the viewer with a short, plastic barrier. Although it doesn’t ruin the experience of the pieces, it does somewhat undermine the taut dynamism central to their existence.

The artist’s Prop Pieces emerged from Verb List, 1967-68, a text work by Serra which lists a series of actions one could conceivably perform while creating a work: “to cut, to flow, to lean, to tear, to mark.” Although not featured within the exhibition, the piece warrants mention as a sort of Rosetta Stone pivotal to deciphering Serra’s artistic modus operandi. Deceptively simple, the list reduces sculptural process to the realization of a few linguistic commands. Through performing these verbs upon a chosen material, he could forego compositional and conceptual plodding and merely witness the results. This brand of process-based sculptural determinism seemed to liberate Serra during this period, allowing the aesthetic and formal elements of his work to emerge without any extraneous intellectualizing.

Descending to the second floor, the viewer is immediately confronted by Serra’s more recent, decidedly more gargantuan work. The cavernous space – one voluminous expanse which houses all three of his newest sculptures – resembles a graveyard for 747’s, the pieces suggesting an ancient pageant of corroded, dismembered aviation fuselage. Constructed with massive, gliding segments of weatherproof steel, the work takes on a deific quality, as if it were an impossibly large metallic ribbon drawn from the core of the earth. The surfaces are velvety with oxidation, exposing an oscillating vista of rusted tones and lending an oddly biological sensation to these industrial titans. Sequence, 2006, easily the largest and most complex piece of the show, invites the viewer into a labyrinthine passageway that can best – if not clearly – be described as a figure-eight which perpetually bends back into itself.

As an object that energetically shapes it surroundings, the work is an undeniably powerful device. But as I investigated the intricate complexities of Sequence, I found myself distracted by the sheer magnitude of it all. I became more fascinated with the work’s impossible largeness than Serra’s stated goal of abstract spatial experience. How were these works created? How were they moved? And most pressingly, how were 550 pounds of weatherproof steel loaded onto the second floor of the Museum of Modern Art without destroying the building? The answers to these questions are undoubtedly dramatic and fascinating, involving herculean efforts by professional rigging teams and an enormously expensive remodeling of the museum’s second floor.

But I found myself yearning for the relative simplicity – and, dare I say, lightness – of Serra’s earlier pieces. They gracefully say everything these new sculptures attempt to shout, without the messy distractions. While the larger works of the second floor are laudable as technical and formal achievements, they say more about Serra’s ego than his creativity. The conceptual wit of his earlier sculpture is all but missing, replaced by an immense brand of self-importance. Of course, Serra has the influence and fame to demand this sort of treatment from one of the world’s premier museums. Unfortunately, his new work cannot endure the hype of the production and Serra’s ubiquitous egotism.

This retrospective is undeniably effective and at times potent, but I wonder whether the groundbreaking scale and the massively burdensome preparation it required obscures the essential point of Serra’s work. It’s a shame, because while the work stays grounded it remains an immutable force in modern sculpture. It’s only when it gets big that the seams start to show.

Richard Serra - Sculpture: Forty Years

The Museum of Modern Art

June 3 - September 10, 2007