Neo Rausch at the Met - para

Who are the ghostly, self-absorbed band of characters central to Neo Rausch’s new show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art? What are they preparing for, and what would they say to one another if they noticed each other’s presence? Why are they dressed like turn of the century dandies, picturesque peasant workers, and vaguely socialist firemen? Rausch, who generated an entirely new cast for this series, isn’t incredibly distracted with predetermined answers to these questions. The artist is more intrigued with the how of these eccentrics: how they come into being and how their visual alchemy creates a quixotic mysticism. As the figures emerge from the lunar miasma of Rausch’s subconscious, they produce a seductively mysterious narrative crammed with enigmatic juxtapositions. Rausch, who titled the show with the incomplete prefix para, is interested in the cascade of associations that his surrealist theater creates within the viewer.

Rausch was trained in Leipzig, where he lived under the East German Communist regime until its collapse in 1989. The Leipzig Academy, which had been in the thrall of figurative painting for nearly two centuries, was abruptly introduced to the conceptual theories and new media techniques of Josef Beuys. Suddenly, artists began to eschew painting and the figure as prosaic and antiquarian. “Painting was the most boring department in the school, and everyone was making jokes about the painters, because they were so old-fashioned in the East German style,” explains Ricarda Roggan, a Dresden-born photographer.

However, Germany has witnessed a return of figurative painting with the emergence of the New Leipzig School, a group of artists who resisted the conceptual legacy of Beuys. Rausch, the most significant figure of the resurgence, refers to himself as “conservative” and “romantic.” He works in the same melancholic, expressionist heritage that includes such essentially German painters as Max Beckman, Ernst Kirchner, and Georg Baselitz. These artists all share a preoccupation with the expressive power of the figure and an obsession with German cultural identity, often characterized with brooding isolation, instinctual naturalism, and the tortured relation between the internal self and an often pernicious external world.

Rausch’s Germanic roots are most on display in Die Fuge (The Gap), an epic phantasm of a painting that mournfully articulates the traumatic schism Germany endured after World War II. Expressions of divide fill the work, from the massive trench that literally dissects that composition to a pair of eerily floating doppelgangers, severed by an effulgent bolt of lightning. A band of fireman dressed in matching uniforms and wrestle fruitlessly with a serpentine hose like a social realist mutation of the Laocoön. Their incompetence reflects the miscarriage of the East German Communist regime, whose ineffectual brand of socialism resulted in economic ruin and cultural decadence. Rausch’s use of stark, deteriorating architectural facades also recalls the economic frailty of Leipzig, where pandemic unemployment has littered the city with abandoned factories.

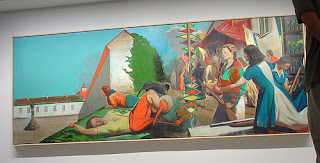

Rausch interest in his cultural past finds expression in Waten auf die Barbaren (Writing for the Barbarians), an image of confounding theatricality and acidic color that presents a group of peasants preparing for a fair. The villagers wear costumes of minotaurs and other chimerical creatures, instilling the proceedings with an oddly portentous air. While the festivities commence, an ostracized townsman is left bound to a sacrificial pyre, presumably to be killed in an act of grizzly immolation. That the other villagers are seemingly unaware of his imminent fate only heightens the painting’s dreadful foreboding, suggesting the façade of willful German naiveté that permitted Nazism and the Holocaust to rage unopposed for so many years.

The looming but nebulous threat of violence is reminiscent of earlier surrealist painting, especially the work of Max Ernst. Ernst, a fellow German who served during World War I, manipulated similar juxtapositions of strange, dream-bred imagery to release the logically devoid subconscious and induce feelings of spectacular unease. While Rausch’s imagery is less overtly fantastical, his foggy milieu is a direct descendent of Ernst’s surrealist phantasmagoria. Vorort (Suburb) exemplifies Rausch’s subtler approach, which is more emotionally suggestive than forcefully evocative. As a jumbled throng of townspeople set fire to flags under a romantically gloomy dusk sky, a nuclear warhead lies calmly isolated opposite their mounting furor. The dormant but massively deadly potential of the warhead stands in stark, lunatic contrast to the villagers and their comparatively benign riot.

Rausch is fascinated by imagery of curtains, fake facades, and costumed players. He sets the stage, then lets his medley of vaguely-defined characters and absurd imagery coalesce into a deranged opera of cultural ambivalence and psychological unrest. “For me, the function of painting… is to work with myths,” the artist explains. “I try to create a widespread system where impulses are trapped. A microclimate comes into being.” Rausch’s surrealist casuistry tells it slant, reinvigorating his German artistic heritage with refreshing wit and insight. The ambiguous theatrics of his fractured narratives explore the mythic German consciousness, defined visually over the past century by the tortured figural paintings of Beckman, Kirchner, Baselitz, and many others. The unique strength of Rausch’s work lies in its ability to pierce this mythology and project it, psychologically fragmented, as a theater of fever dreams and violent fantasies.

Neo Rausch at the Met- para

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

May 27, 2007 - October 14, 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment